Strategic Change and Canadian Shipbuilding

There is an increasing amount of commentary about the National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS). This discussion is mainly connected to the production by Chantier Davie of MV Asterix, a converted ship that will be leased to the Royal Canadian Navy as a replenishment ship for five years. The completion of this ship is taken by some observers as ‘proof’ that the NSS should reopened to allow work from one or both of the two selected NSS shipbuilders to be diverted to the Davie yard.

The argument in favour reopening the strategy is generally that neither the Irving nor Seaspan shipyards are operating efficiently and that the ships being built by them do not satisfy the most important requirements of either the Coast Guard or the Navy. That the largest Coast Guard icebreaker is nearly 50 years old and the Type 1200 icebreakers were built in the 1970s are cited by critics to show that the sequencing of the two building programs is flawed. In addition, resistance to the adoption of the Harry DeWolf-class Arctic and Offshore Patrol Vessels by the Navy is still ongoing. In this regard, we hear again the opinion that the Navy has no need of such vessels and the highest priority requirement is for destroyers.

The problem with such criticism is that none of it is actually strategic in nature. Mostly it pertains to a defence of the status-quo for a naval force structure born in the Cold War and for a coast guard mission that dates back to its formation in 1962. Most commentaries are about programmatic organization and practical outcomes rather than strategic issues and trends.

The strategic assessment conducted before the shipbuilding strategy was announced was managed by a multi-departmental team of senior leaders and was assisted by contracted external advisors. They looked at all factors relating to the basic statement that “the ability to use the sea in important to Canada,” and the derivative conclusion that “Canada will build the ships needed for out maritime requirements.” The factors examined in the preamble to these strategic conclusions included a wide variety of trends pertaining to history, politics, economy, geography and technology.

The strategic conclusions from the assessment were basically threefold. First, that Canadian industry could conduct such work and historical evidence existed to that effect. Second, that there was enough work required that a continuous building program could be organised to sustain two shipyards. Third, the state of the industrial infrastructure and work force was below the standard required.

The deductions from the strategic assessment led to a competition between all Canadian shipyards for the two main contracts. The assessment indicated quite clearly that there was an industrial overcapacity and ‘right-sizing’ was required to match means to needs. Two companies were selected on the basis of a complex scale of assessment criteria. While the exact details of the criteria and weighting factors have not been made public, a general interpretation of the outcome was that Canada’s situation could be satisfied by two medium capacity shipyards. As a result, Irving Shipbuilding and Seaspan were chosen for the combat and non-combat constructions streams respectively. Both had to undertake significant upgrading of their infrastructure and workforce. To test and analyse their new capabilities, the building programs were organized to begin with simpler projects, rather than take the risks associated with more advanced ones, despite the evident need. The first ships by both yards are on time and within budget.

In my view, there is no requirement to reopen the strategy or to challenge decisions made to this point. To do so should mean that fundamental changes to the strategic situation of the country have occurred. That is not the case. The security, stability and economic viability of Canada are essentially the same now as they were at the time the shipbuilding strategy was announced. Trends have accelerated in some cases, such as the warming of the climate and the development of some international security concerns, but none of them merit the declaration of an emergency that would have impacts on the strategy itself.

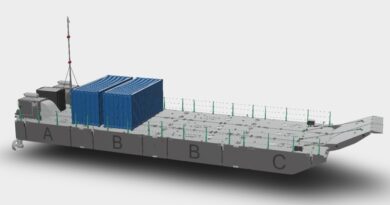

Even if an emergency of strategic consequence did arise, the first reaction by government should be to discuss with the two contracted shipyards what their capacity for faster and greater output might be. The conversion of MV Asterix is a stop-gap measure with a used ship that will keep important naval skills alive. Meanwhile, the main effort will provide new and purpose-built ships that meet the specifications set out by the government. In my opinion, the ship built by Davie does not represent a response to a need so great that the strategy should be reopened.

A PDF of this Comments is available here.

Ken Hansen is a retired officer of the Canadian Armed Forces. He was the Military Co-Chair of the Maritime Studies Programme at Canadian Forces College in Toronto before becoming a resident research fellow at the Dalhousie University Centre for Foreign Policy Studies and then being appointed as Adjunct in Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science. He is a member of the Science Advisory Committee for Atlantic Oceans Research Enterprise and has been a contract researcher working on shipbuilding costs for the Parliamentary Budget Officer.