Why Pilot Training Production for the RCAF is Failing and Why are Pilot Losses Mounting

Background

Prior to the integration of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in 1966, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) maintained a robust pilot training system run by RCAF Training Command. When the Commands within the air element of the CAF were disbanded, Air Groups were introduced for the Fighter, Maritime, Transport and Air Reserve communities but training became a subset of the newly formed Air Command. In the quest of finding new ways of saving money, Air Command’s plan was to contract out services under the belief that money would go further if dollar amounts were applied to everything – such as the cost of life cycle management, lighting in hangars, the cost of salaries, cleaning services, messing, et al, to name but a few. As a result of this ‘new thinking,’ National Defence Headquarters (NDHQ) and Air Command introduced contract pilot training. In this paper, we will not deal with the multitude of changes which took place from 1967 through 1995. However, the bottom line is that Air Command retained the two major air training bases at Portage La Prairie and Moose Jaw, the two locations where primary, basic and advanced flying training take place.

Contained in the new plan was the introduction of contract services for all aspects of training operations, maintenance, infrastructure and logistic requirements. With this change came new aircraft, simulators and a new way of training future officers for the RCAF. The only aspect which stayed the same was that the flying instructors were serving CAF members.

The Current Situation

Today, pilot training is contracted out under a program known as NATO Flying Training in Canada (NFTC). Training for all pilots is conducted in three phases: Phase I is ab initio training conducted at Portage La Prairie on the Grub G 120A piston aircraft; the phase is basically a selection process. All successful students then move onto Phases II and III.

Phases II, III and IV are carried out at 2 Canadian Forces Flying Training School (CFFTS), 15 Wing Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, and at 4 Wing, CFB Cold Lake, Alberta. The program is delivered as a cooperative operation between the current civilian contractor, CAE Inc. (CAE Training Centres), and the RCAF. This contract is due to expire in 2024.

The two types of aircraft flown are the CT-156 Harvard II and the CT-155 Hawk. NFTC training consists of Phases II, III, and IV. Phase II is subdivided into IIA and IIB. All pilots in the NFTC program undertake Basic Flying Training, known as Phase IIA, which consists of 95 flying hours on the CT-156 Harvard II, a Pilatus tandem two seater turbo-prop aircraft. After this phase, students are split into three streams: fast-jet (future instructors and/or fighter pilots), multi-engine and helicopter trainees.

Those destined to become helicopter and multi-engine pilots move on to Phase III training at 3 CFFTS in Portage. Those selected to become fighter pilots complete Phase IIB consisting of another 45 flying hours on the Harvard II. These candidates then move on to Phase III, also in Moose Jaw, which consists of an further 70 hours on the Hawk. On completion of Phase III, pilots are awarded their Pilot’s Wings (both at Moose Jaw and those at Portage).

Future fighter pilots move on to Phase IV, still on the Hawk, conducted by 419 Tactical Fighter Training Squadron in Cold Lake. This phase consists of 49 flying training hours. Successful graduates of Phase IV are then posted to the CF-188, commonly known as the CF-18 Hornet, at 410 Tactical Fighter Operational Training Squadron, also located at Cold Lake.

The division of responsibilities between the Department of National Defence (DND, the RCAF, and CAE are as follows:

- RCAF: All in-aircraft flying instruction is given by RCAF pilots. DND oversees training standards, provides military trainees (both RCAF and NATO), provides the airspace and dictates the syllabus. As an aside, any future planned flying training syllabus should also be examined. For example, what is the emphasis placed on formation?

- CAE: The NFTC aircraft are owned by the Government of Canada, then leased to and maintained and serviced by CAE. Academic and simulator instruction is given by CAE employees, who must have had previous military flying instruction experience. CAE also operates infrastructure (buildings) and provides food services.

Other Air Forces participate in our pilot training program, hence the NATO title. International program management, foreign military flight instructors, foreign military students, and quality control are also part of the current plan.

The current system is intended to provide between 110 and 115 pilots per year. It is not known by this author if there is a surge capacity built into the program, but there certainly should be one in case of mobilization or crisis. The bottom line is that the current program production is inadequate as the RCAF is facing a shortage of some 150 pilots and looking for furloughed airline pilots to replenish the ranks is not a viable solution.

Recruitment

It is no secret that the staffs at Air Command HQ and NDHQ are attempting to find remedies to solve the pilot shortage. However, they may have to swallow a bitter pill to find the solutions which have heretofore been rejected. Here are some of the factors which could be addressed:

- Why could the RCAF not re-introduce a short service commission (SSC)? Pilots who do not want a lifelong career in the Air Force might find this attractive. Another alternative which could also as be attractive as a five year SSC could be a 20-year flying career with guaranteed flying only, no desk jobs or career advancement.

- University degrees. Not every pilot needs to have a pathway to becoming a General, some may just want to fly (what a quaint idea!). Does every pilot have to have an undergraduate university degree? A review of minimum educational requirements should be undertaken. Minimum criteria could be set as university entrance education for those who only wish to undertake a flying career and not aspire to be a career officer as suggested in subpara a above.

- Officers streamed through the military colleges or direct entry university graduates who wish to pursue a full career would continue as is the current situation which provides career development courses, ground jobs and high profile command positions.

- Make full use of Reserve officers. There is a strong talent pool out there that we tend to ignore. Airline or other current pilots who are enrolled in the Air Reserve should be allowed to fly operational aircraft on a rotational basis. Bias against them should be eliminated and allow full integration into front line squadrons. Scheduling would have to be carefully maintained. This is discussed below.

- Upon release from the RCAF, pilots should be automatically enrolled in the Air Reserve. Details concerning this avenue should be addressed.

The Retention Problem

Why are so many motivated, experienced pilots leaving the RCAF? There are many factors involved here but there are certainly some gaping examples of where nothing has been done to address the issue. Based on conversations with many pilots who have left the service, pay and pay raises are not the issue. What is? Their lifestyle.

As mentioned above, one of the criteria for pilot training is having an undergraduate degree. These candidates are more mature than the person who only has a secondary education but is also older. This is a big factor as many new pilots have married other university graduates and herein lies a major problem: postings to semi-isolated locations.

There are some major observations from serving pilots at these isolated bases, i.e., Cold Lake and Bagotville. There is much concern that morale at these bases amongst the pilots is low, and many of them have sent resumes into the airlines (this may have changed with the advent of the economic downturn as a result of COVID-19 ). They feel they are stuck in the wilderness for most of their careers (Europe is no longer an option). Others expressed concerns which are family related. Since many pilots have married spouses with their own careers, these spouses wish to work and continue with these professions, and this option is not normally available (unless you’re in a medical or teaching field). Is there a solution to this major problem? Sure there is, there always is if there is a will to fix it. Try this on for size.

Interested readers may recall that back in the early eighties there was talk of making Namao (Edmonton) a fully operational base, and still fly missions to the current training areas, whilst families all lived in Edmonton. The mayor of Edmonton squashed that idea and reminded DND that Namao would be closed as an airbase by 1990 – and that came to pass. Most airlines allow crews to live anywhere on their route structure, and they commute to work when scheduled. Perhaps a similar system would work to mitigate the issue of living ‘in the boondocks.’ The RCAF just needs to re-introduce scheduled flights (SKED FLTS) using a number of transport type aircraft tasked for the role, for example, using the CC-295 Kingfisher or CC-130 Hercules. In finding a solution to the problem, the SKED FLTS could be planned to operate out of Edmonton (for the Cold Lake personnel) and Montreal or Quebec City (for Bagotville personnel). Comox does not appear to present the same situation for families, neither do Trenton or Greenwood.

Other Observations

Training pilots is only one part of the puzzle. Retention is the more significant issue. It costs a few million dollars to train a pilot to operational status. If those pilots cannot be retained, fully manning the squadrons cannot be maintained. In days of yore, the numbers game anticipated both the ‘failure rate’ during training and the loss rate after a Short Service Commission. I recall during my time in the RCAF/CAF, pilot intakes had about 50 people or so and there were 16 intakes every year. There is no way that these numbers will ever return, but the concept of increased applicant flow needs to be addressed if DND wants to solve the manning problem. As mentioned above, just what is the maximum output capacity of a future aircrew training program?

As an interesting aside, Apple, Google, IBM, and Microsoft can no longer afford three-four year computer science degree people who finish the academic program with obsolete training. The curricula in most universities is about two years out of date with current technological advances; so those high tech employers have started their own ‘university’ program which takes bright high school kids who are tech-savvy, and then are trained by the company to be productive in about six months. I refer you to a YouTube article called “College is a waste of time” by Bet-David. The pilot recruits might fit into the same type category.

One crusty retired air force pilot told me this: “I remember back in the late ’50’s when I struggled with algebra – I put in 30 years as an aircrew officer, acquired two degrees, and I haven’t used algebra once!!”

What Does The Future Have In Store, Post NFTC?

The federal government’s Future Aircrew Training (FAcT) Program, which is currently awaiting the release of its draft Request for Proposal (RFP), is an ambitious solution to Canada’s military aviation needs. The Public Services and Procurement Canada FAcT website describes its goal succinctly: “The program will renew aircrew training services to help maintain a multi-purpose and combat capable air force. The program will include delivery of pilot training, as well as aircrew training for air combat systems officers and airborne electronic sensor operators.”

To make this happen, whoever wins the multi-billion dollar FAcT contract (a firm number has yet to be released) will have to merge Canada’s two existing military aviation training programs into one. The first is the NATO Flying Training in Canada program, already discussed, under private contract until 2023 with a possible one-year extension option.

The second is the Contracted Flying Training and Support program whose private contract runs until 2027. As well, the FAcT winner will have to offer the full range of training requirements at 15 Wing Moose Jaw, and Southport (formerly known as Canadian Forces Base Portage la Prairie), and at 17 Wing Winnipeg, where Air Combat Systems and Sensor Operator Training is currently conducted exclusively by the RCAF (2 Air Division) but is intended to blend into FAcT.

On 10 December 2018, the federal government announced a select group of qualified suppliers to bid on the FAcT program that has since dropped to four. They are: Babcock Canada, Leonardo Canada, Lockheed Martin Canada and the SkyAlyne Canada Limited Partnership (SkyAlyne Canada/SkyAlyne).

Of these four, SkyAlyne Canada would seem to have an inside edge. The reason: SkyAlyne is a 50/50 partnership between CAE and KF Aerospace, both of whom have experience in training Canada’s military pilots and aircrews. This is because CAE is currently managing the NFTC program, whilst KF Aerospace is managing the CFTS program.

We now await the government/DND decision to see which program will be introduced post NFTC.

Conclusions

It goes without saying that the RCAF pilot crisis requires a need for total examination of recruitment, training, motivational factors and retention. In this paper, we have made some suggestions which should be taken seriously if the RCAF is to maintain the required strength in the number of pilots required to maintain operational readiness for all pilot communities: Fighter, Transport, Maritime and Rotary Wing.

To review, here are some of the most glaring shortfalls to be examined:

- The current through-put and surge capacity to produce trained pilots;

- Motivational factors, aircrew/family locations and quality of life;

- Continuation training, recalls and alerts and deployment factors. This needs to be clearly spelled out with respect to any domicile or home basing system and the introduction of programmed scheduled flights;

- Re-introduction of a dual-stream career plan, Short Service Commission and career officer;

- The Short Service Commission option for those who only want to fly. A program option whereby after the fourth year of service, those who wish to pursue a career (permanent commission) could be offered university training at RCAF expense. Of necessity, fixed extension terms would be available for selected pilots based on the requirements at the time;

- After completion of the Short Service Commission, automatic transfer to an active ready Reserve status available in times of crisis;

- Education. As currently exists, only university graduates (civilian university and military college) can apply for pilot training. Should this change, consider the need to re-introduce direct entry short service term enrolments with certain qualifying requirements – formal schooling (what level?), some community college, et al. What about candidates who currently possess a commercial pilots licence?; and

- Finally, a look at syllabus training, advanced training skill requirements. When do you stream (rotary, transport, fighter) and when would the students be selected? Would they have a choice on enrolment? Motivational – I would like to be a XXX pilot. Selection criteria will be most important.

Recommendation

The Royal United Services Institute of Nova Scotia has realized for some time that a crisis exists in the recruitment and retention of pilots in the RCAF. To this end, the Institute’s Security Affairs Committee has written this paper with a view that planners at 2 Air Division and the Air Staff at NDHQ set up a task force to deal with this continuing crisis. We look forward to hearing the outcome of our suggestions.

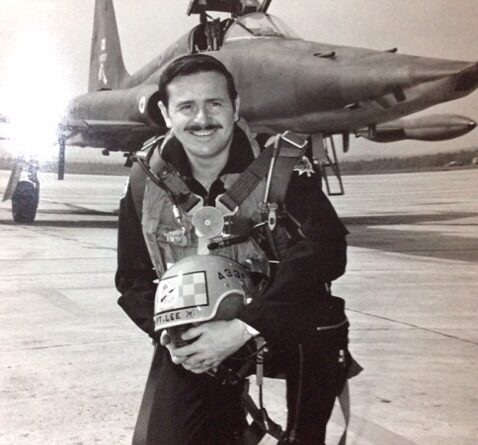

Recommended citation: Murray Lee, Why Pilot Training Production for the RCAF is Failing and Why are Pilot Losses Mounting, Royal United Services Institute of Nova Scotia, March 20, 2021

Murray Lee is a retired RCAF pilot with extensive experience flying fighters. This work is the sole opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of the Canadian Department of National Defence, the Canadian Armed Forces, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or the Royal United Services Institute of Nova Scotia. The author may be contacted by email at: RUSINovaScotia@gmail.com.