No. 2 Construction Battalion: A Short History & an Apology

On 25 May 2022, Colonel (retired) John Boileau, spoke to RUSI(NS) and guests with a presentation titled “No. 2 Construction Battalion: A Short History & an Apology.”

After considerable lobbying by Blacks and white supporters, Canada fielded one Black battalion during the First World War — but they had to fight with shovels, not rifles. No. 2 Construction Battalion was authorized on July 5, 1916, in Pictou, NS, and was composed of Black men from across Canada, the United States and the British West Indies. Its officers were white, with the exception of the unit’s chaplain, Honorary Captain The Reverend William Andrew White. The battalion went overseas in March 1917 and served in France’s Jura Mountains, near the Swiss border. It spent the war attached to No. 5 District, Canadian Forestry Corps, producing the critical wartime commodity of lumber. Facing prejudice and rejection, the men of No. 2 persevered to play their part in ‘the war to end all wars.’ The story of the unit is an important, but largely unknown, part of Canada’s military history. In March 2021, the Minister of National Defence outlined the Government of Canada’s intent to apologize for the treatment that members of No. 2 Construction Battalion endured before, during, and after the First World War. The presentation included the history of the unit, as well as the apology process.

Following is the text that Colonel Boileau used for his presentation. A PDF of this text is available on request. A PDF of Colonel Boileau’s presentation slides is available here.

Note: S1, etc., in square brackets refers to slide numbers.

[S1] Good day everyone and thank you for joining us for this video presentation. A special welcome as well to those from outside Halifax who are able to attend because we’ve moved to a Zoom presentation, rather than an in-person one. I know that many of us are suffering from “VTC fatigue” during the pandemic, but it certainly is a way to reach a much wider audience than usual. Please note that all slides in my talk are numbered in the lower right corner, should anyone want one recalled for discussion later.

[S2] I have researched, written and talked about No. 2 Construction Battalion on several occasions. Here is what I will talk about today: after a brief description of my connections to No. 2, I’ll give a quick summary of Black Canadians in the First World War (FWW), the formation of a Black unit and why it was a construction battalion and not an infantry battalion, No. 2’s role overseas, the end of the war, quite a bit about remembrance and various centennial commemorations in 2016, a big picture view of No. 2’s overall role, and conclude with the national apology process as led by the National Apology Advisory Committee—the NAAC.

[S3] Why am I qualified to talk about No. 2? Well, here it is: 1. regular military service for 37 years and another 10 as an Honourary; 2. writing and presenting, mostly historical non-fiction, largely military history (books/articles/public talks/radio-TV-newspaper interviews—not quite infinite, but I’ve lost count); 3. direct connections with No. 2: Centennial Planning Committee alongside BCCNS (Black Cultural Centre of Nova Scotia) directors, Douglas and Lindsay Ruck, son and granddaughter respectively of Calvin Ruck, author of The Black Battalion, provincial government representatives and several others; member NAAC and two of three main sub-committees (Communication & Public Outreach, History & Public Education). I’ve also written 10+ articles about No 2 as shown on the slide for local publications such as the Halifax Chronicle Herald, now defunct Halifax Daily News, Royal NS International Tattoo and national ones, such as Legion Magazine, ANAVETS Magazine, The Canadian Encyclopedia; given a half-dozen talks and presentations; attended numerous events; and acted as liaison between National Defence Headquarters and the BCC for perpetuation of No. 2, which I’ll explain later. I would also like to publicly acknowledge the work of recently-retired NDHQ/Directorate of History and Heritage historian Major Mathias Joost, whose research has uncovered many of the facts and figures I use in this presentation. Mathias also serves on the NAAC and co-chairs its History Sub-Committee.

[S4] Here are a couple of examples of my written articles about No. 2: Legion Magazine cover story and Royal NS International Tattoo souvenir program, both in July 2016 on the unit’s centennial. By the way, I should mention here that the name of the unit is No. 2 Construction Battalion, and not “the” No. 2 Construction Battalion, as many people incorrectly state. Just as we don’t say “the” Dalhousie University, we don’t say “the” No. 2.

[S5] During the FWW, there was no government regulation that specifically prevented Blacks from joining the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). But at unit level, it was a “Catch-22” situation and Commanding Officers (CO) and recruiting sergeants took it upon themselves to deny Black enrollment. All attempts to form Black units or sub-units (platoon/company) failed. Here is what some white officers said:

[S6] On the left is what Lieutenant-Colonel (LCol) George Fowler CO 104th (New Brunswick) Battalion, CEF, wrote in an attempt to have 20 new “coloured” soldiers removed from his unit (pause)…and on the right what the Chief of the General Staff—the highest uniformed position in the forces—wrote (pause).

[S7] Finally, on the direction of Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia and Defence, the government clarified the issue, but left it up to unit COs—right back at the level that was denying Blacks to join. Despite this confusion, amazingly apart from the 760 who initially enrolled in No. 2, about another 300 to 500 Blacks somehow managed to enroll in CEF out of the populations shown—although there could be more. This includes 110 who served in the front lines. As an aside, 10 of those 110 were awarded decorations for bravery in battle: 2 Distinguished Conduct Medals (second only to the Victoria Cross), 1 Military Cross and 7 Military Medals (soldiers’ equivalent to officers’ Military Cross)—an incredible percentage. It’s virtually impossible however, to ascertain a soldier’s ethnicity or race from his service file, as these were not identified. It could be that the total enrolled is higher. It would be a fruitful area of research to try and determine the definitive number of Black soldiers who served in the CEF.

[S8] Finally, after extensive lobbying by Black community leaders, as well as some supportive whites, the government authorized an all-Black unit on July 5, 1916. The unit formed was No. 2 Construction Battalion, one of 3 construction battalions Canada formed during the First World War, a type of unit no longer used today, but very much in demand during the war. Construction battalions carried out essential non-frontline tasks such as building and repairing rear trenches, roads, bridges and railways, among other duties. Most CEF units were city or province based and given NS had the largest black population in Canada at the time—more than 1/3, some 7,000 of 20,000—it was chosen as location to mobilize the new unit. Pictou was selected, as close to the home of the CO, LCol Donald Sutherland. No. 2 was the first and largest post-Confederation segregated unit. The officers were white, except for the unit chaplain, Reverend William Andrew White, and the two most senior Non-Commissioned Officers (NCO) appointments in the unit: the Regimental Sergeant Major and the Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant Major. The unit moved to nearby Truro after two months in Pictou.

[S9] No. 2 was the first, but according to recent research, not the only post-Confederation segregated unit. Mathias Joost has discovered another. Late in the war, the Canadian Forestry Corps (CFC) designated seven companies for airfield construction on the continent. No. 8 Company, mobilized in July 1918, consisted of five white officers and eleven NCOs with 169 Black soldiers, which included seven transferred from No. 2, as shown here. These companies cleared, drained, levelled and graded sites for aerodromes, as well as restoring captured German airfields to operational status for Allied use. No. 8 Company remained in Germany until March 1919; the last CEF unit to leave Germany. In No. 7 Company, another airfield construction company, 15% of its soldiers were Black.

[S10] For orientation (and I believe there is no good military history without good maps), here are the locations where No. 2 or sizeable detachments were stationed in Canada and which I’ll mention in this talk: 1. Pictou-original location 2. Truro-new location two months later 3. Windsor and Toronto, Ontario, collecting points for some Ontario and US recruits 4. NB detachment in early 1917 to lift rails 5. Halifax-departure for the UK.

[S11] There was criticism reportedly at time and certainly today that No. 2 was not a front-line or combat unit due to racism (read quotes). but it would have been impossible to raise a Black infantry battalion in NS or all of Canada, as there were insufficient Black males available based on the population.

[S12] In 1920, Capt M Stuart Hunt compiled “Nova Scotia’s Part in the Great War,” which summarizes what every unit raised in Nova Scotia did during the FWW, as well as several civilian support organizations. I say “compiled” rather than wrote, as chapters were written by officers from the units concerned. We know the CO No. 2, LCol Sutherland, actually wrote this chapter as his granddaughter has a copy and Stuart thanked Sutherland in the preface. Here is a quote from the second paragraph in the chapter as to why it was impossible to recruit and sustain an infantry battalion (read). So…bear with me and let’s look at the numbers: Nova Scotia’s Black population was 7,000, half were males=3,500. 37% of the Nova Scotia male population that was age eligible (18-45) served. If this percentage holds true for Black males, then 1,305 were available of all ages (I do not know the numbers of only age eligible Black males). This number is reduced by essential workers and the medically unfit. 200 Black coal miners were deemed essential war workers and not allowed to enlist—some sources state this number was as high as 400. There were also 400 Black munitions workers in the Maritimes, another essential industry whose members could not enlist. Medically unfit numbers are unknown, but an individual could be rejected for several medical conditions or even simpler problems: poor eyesight, too short, insufficient chest expansion, obese, hard of hearing, bad teeth, flat feet and several other reasons; So, conservatively, let’s say 100 (although likely higher), totaling 300 and leaving 1,005 available, less of course under and over age. An infantry battalion had 1,049 all ranks, but required reinforcements due to death from combat, accident and sickness; due to wounds, injuries or sickness serious enough to remove from unit; or missing and Prisoners of War. In the case of the 85th (Nova Scotia Highlanders) Battalion, which entered combat at Vimy Ridge in April 1917—the month after No. 2 arrived in France—it required 2,736 reinforcements in the last 19 months of war, resulting in 3,785 soldiers required to keep the unit manned up to strength. Again, only 1,005 Black men were available in Nova Scotia at the absolute most. If we look nationally—and using the national percentage of 40.3% of age eligible males, then 4,030 Black males were available of all ages, a number further reduced by essential workers, medically unfit, previous enrollments and those with no desire to join, plus of course those under and over age. So, clearly, neither Nova Scotia’s nor Canada’s Black male population could have supported an infantry battalion at the front. And even if somehow an infantry battalion had been formed earlier in the war and sent into combat, the situation would have been even worse, as many of first infantry battalions in combat required 4,000-5,000 reinforcements. It was clearly racism that prevented Black men from joining the CEF, but in my opinion it was simply the numbers of available Black men that led to the formation of a non-combatant unit, and not racism. But: Catch-22—on the other hand, if the Black male population of Canada had been sufficient to man and reinforce an infantry battalion, a very different situation could have developed, because the British War Office refused to allow any Black units into combat on the Western Front. While the reason certainly did not apply to Canadian Black men, authorities feared that training Black men from the colonies where Black populations were in the majority might use their training and combat experience to overthrow colonial administrations after the war. I don’t want to get too far off track here, but in fact, the only non-white troops the British allowed to fight on the Western Front were two Indian divisions hurriedly transferred there after the British Expeditionary Force suffered heavy casualties in the opening battles of Aug 1914. These divisions also contained battalions of Nepalese Gurkhas, long admired by the British for their fighting abilities.

[S13] Recruiting was carried out across Nova Scotia wherever a Black population existed and the unit had 180 recruits in Pictou by Aug 19. but recruiting quickly slowed down, so the battalion moved to Truro two months later. The CO thought the move might help with recruiting as Pictou did not have any Blacks living there, while Truro did. There was also more barracks room available in Truro. No. 2 formed a band with donated musical instruments, which proved highly popular and conducted concerts as part of recruiting drives across Nova Scotia. Due to lacklustre recruiting results in the province, Sutherland also recruited across Canada, making No. 2 truly a national unit. Eventually 760 soldiers enrolled in No. 2, but some were released for various reasons before going overseas or later.

[S14] The nominal roll (actually the sailing list) of the battalion is held at the Nova Scotia Archives and is available online, as of 7-10 days prior to sailing overseas in March 1917. Although it contains errors (only 611 actually sailed), it reveals the following numbers (read). Sutherland had hoped to recruit two companies in Nova Scotia, one in Ontario and one out west. As it turned out, only “A” company was formed outside of Nova Scotia, and was based in Windsor, with a large contingent from Toronto. The final total was only about 60% of that required for the battalion, so we must ask…why?

[S15] There a number of possible reasons: the segregated nature of the unit, the fact that it was not a combat unit (which I have just shown would have been impossible to man in any case) and stationed well behind front lines or because those who had suffered rejection earlier refused to try again. And there was another big Catch-22: once conscription became the law of the land in Aug 1917, Blacks, including those who had been rejected previously, could be conscripted and suffer punishment if they refused, such as forcible induction or severe penalties. At least 360 of the 125,000 Canadians who were conscripted were Black, but it could be as high as 500. Of the 125,000 conscripted, only 25,000 in total made it to the Western Front.

[S16] These are probably the two most important officers in No. 2 and certainly the ones we know the most about: the CO, LCol Dan Sutherland and the chaplain, Honorary Captain Reverend William Andrew White. Sutherland was a prominent railroad contractor, who had previous militia service and who joined 193rd (Nova Scotia Highlanders) Battalion in Apr 1916, which recruited in eastern Nova Scotia with headquarters in Truro. After much searching, Sutherland accepted the appointment as CO No. 2, providing the unit could mobilize at Pictou, near his home in River John.

The chaplain, the Reverend Doctor Andrew White, was Black; one of only nine Black officers in the CEF during the war. As a padre—like all other chaplains in the British Empire—he was not a commissioned officer as his captain’s rank was honorary: he wore the three pips of a captain, was entitled to be saluted and addressed as “sir” by lower ranks, but had no command authority (I was an Honorary Colonel for 10 years—even though a retired regular force Colonel with 37 years service, as an Honorary Colonel I had no command authority). In Canada, military chaplains were honorary during the FWW, through the Second World War (SWW) and into the Korean War, even Padre John Weir Foote, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions at Dieppe during the SWW. White was from Virginia, the son of a slave. He moved to Nova Scotia in 1900, studied theology at Acadia University and became its second Black graduate. He later moved to Truro, where he was pastor at the Zion Baptist Church.

[S17] Before departure, No. 2 was tasked with a mission to help the war effort. In January, February and early March 1917, a company was sent to New Brunswick to lift rails at sidings in Moncton, Nappadogan (north of Fredericton) and Edmundston, to be shipped overseas to Western Front.

[S18] Despite being understrength, military authorities asked Sutherland in December 1916 if No. 2 was ready to be sent overseas. He said the unit was prepared and the Windsor detachment joined the unit in Truro (shown here) two weeks before departure.

[S19] Unbelievably, Canadian military authorities tried to keep No. 2 segregated even while being transported overseas and suggested sending the unit on its own ship. Fortunately, the Royal Navy (RN) rejected this idea and No. 2 embarked in His Majesty’s Transport Southland on March 25, 1917, along with about 300 soldiers from other units and with Sutherland in overall command. Great care was taken during the crossing to guard against enemy U-boats: no lights were shown, no bugles blown and day/night watch kept for floating mines and subs. Southland had been torpedoed in the Aegean Sea in Sep 1915, but was refloated and repaired. Also, during the week of Southland’s voyage, April 1 – April 8, more ships were sunk than at any other time during the war. Southland arrived safely in Liverpool on April 8, but on June 4 it was torpedoed off the Irish coast—the same route that No. 2 had used two months earlier. This time the ship was not recovered.

[S20] Again, for orientation, here are the locations where No. 2 or sizeable detachments were stationed in Europe and which I’ll mention: 1. Liverpool, where the battalion arrived 2. Seaford Camp, where it was stationed for 6 1/2 weeks 3. La Joux, where it spent time in France, except for: 4a. Péronne, detachment November 12, 1917 – December 7, 1918 and 4b. Alençon, detachment for almost the same period.

[S21] On arrival in Liverpool, the troops immediately entrained for Seaford Camp on the Channel coast of Sussex, a major location for Canadian soldiers during the FWW. At Seaford, soldiers of No. 2 were escorted by a British band to their tented camp about two miles away. At this time, soldiers of No. 2 were placed in isolation for 10 days like all troops arriving from Canada to prevent the introduction of any contagious diseases.

[S22] At Seaford, the unit provided working parties to build trenches for troops in training and to build and repair roads within the Canadian lines. About May 1, as result of frequent enemy air raids, permanent air sentries were detailed to watch for and react to enemy Zeppelins, which had been raiding southeast England. The war was suddenly very real. During a Canadian Army sports competition at Seaford, members of No. 2 won a silver cup presented by the British YMCA.

[S23] Before any unit could be sent to the continent, it had to be up to strength. As No. 2 was understrength by about 400 soldiers, it was downsized to a company of 504: 495 soldiers and 9 officers, and renamed No. 2 Construction Company. Here are Nova Scotia cousins George and James Downey, an example of some of the many brothers and cousins who often joined together. 89 soldiers were left in the UK, 67 of whom later joined the unit in France, while the remainder were posted to CFC companies.

[S24] Here are the officers pictured later in France. In the photo on the left, Sutherland is seated on far left of front row, while White is seated front row centre. In the right photo, the CO is near the centre, 4th from left, and the chaplain is 4th from right. Although renamed as a company, today it continues to be referred to No. 2 Construction Battalion, its original name. Because companies are commanded by majors, LCol Sutherland voluntarily reverted to major so he could remain with the unit.

[S25] No. 2 was ordered to proceed to France and at 2 am on May 17, 1917, it took a short train ride from Seaford to Folkestone, where it embarked on a channel ferry to cross to France. During the 2 hour crossing, No. 2 was escorted by 2 RN destroyers and a dirigible on the lookout for enemy U-boats. The unit arrived at Boulogne at 3 PM. After 24 hours at a rest camp, it travelled by road and rail to Lajoux in the Jura Mountains of eastern central France, in the wooded foothills of the Alps, near the Swiss border, arriving on May 21. The first 10 days were spent in quarantine due to a case of measles, although the men worked.

[S26] The company was attached to No. 5 District, CFC. Lumber was a very critical commodity during the FWW, more so than in later wars. It was used for revetting the sides of trenches, duckboards for the bottom of trenches or across muddy terrain, artillery gun platforms, railway ties, ammo boxes, accommodation huts and many more uses. The war strained shipping space, so Britain and France reduced timber imports by using their own forests. And they turned to Canada for the necessary logging skills. Initially forestry battalions were formed, but these proved too unwieldly for the job, so companies were chosen as the basis of CFC organization. Eventually 101 Canadian forestry companies were formed, working in Britain and France. Altogether, these companies employed 22,000 soldiers, plus 9,000 attached personnel (such as No. 2), bringing the total to 31,000 Canadians involved in forestry operations.

[S27] No. 5 District had only been established a few weeks before No. 2 arrived, so initial accommodation was in tents as shown on the left (note the duckboards as a wet spring that year). Proper wooden huts followed by October 1917 as shown on the right. Certainly, by the standards of men fighting, living and dying in the horrible conditions of frontline trenches, soldiers engaged in forestry operations lived in comfortable camps such as this. Cookhouses, barracks and mess halls were light, spacious, well-heated and dry; the dryness assured by copious amounts of readily-available sawdust. Playing fields were laid out and sports days held regularly to maintain morale.

[S28] Fortunately, the company had its own 6-bed hospital and Medical Officer (MO), Captain Dan Murray. Murray treated all men of No. 2 equally but occasionally, when he was away, other white MOs refused to treat soldiers from No. 2.

[S29] The heart of each camp was the mill, powered by a 180 hp steam engine. It was fired by wood chips and drove several different types of saws. Nearby were stables housing the many horses that plodded through the woods, hauling immense logs to the mill. There were four forestry companies consisting of 170 men and 40 horse teams located within 800 metres of No. 2’s camp. Each day the men of No. 2 paraded to be detailed to assist in forestry operations. All lumber sawn by the companies was shipped from the Lajoux railway station by No. 2 and went to the French Army, as the area was in the French Army’s zone of operations. 50 men assisted No. 22 Company in logging and constructing a narrow-gauge railway to transport logs to the mill. A party of 100 men kept the roads in good repair, using a road plant consisting of a rock crusher, steam drill, trucks and steam roller. Due to heavy traffic and the mountainous terrain, good roads were vital to forestry operations. The unit also used anywhere from 70 to 100 horses in terrain too rough for vehicles.

[S30] As in all army units, some soldiers of No. 2 got into trouble and, depending on the charge, would spend a few days in jail. The Officer Commanding No. 5 District CFC had No. 2 soldiers construct this log jail shortly after the unit’s arrival. Soldiers who were found guilty of certain charges—defaulters as they were known—could spend up to 28 days in jail, depending on the seriousness of the charges.

[S31] The soldiers worked hard and Chaplain White’s diary reveals his constant concern for their well-being. Despite being engaged in war work, the soldiers were frequently treated like second-class citizens.

[S32] The officers also had a mess constructed for their use as shown in these photos. In the right image, the mess is decorated for Christmas 1917.

[S33] In late 1917, No. 2 provided 2 detachments to other CFC locations in France, where they provided similar work to Lajoux. On November 12, 54 soldiers were attached to No. 37 Company near Péronne in northeastern France.

[S34] During the great German spring offensive of 1918, these soldiers were the closest anyone in No. 2 came to the enemy. While German shells fell in the area and the Germans closed to within 2 kilometres of their camp, the soldiers buried important parts of their mill machinery and withdrew westwards on March 23. The second detachment arrived at Alençon in northern France on December 31, consisting of 2 officers and 180 soldiers. They were attached to the CFC’s No. 1 District, where they were split up among 4 different companies. The soldiers of these detachments remained there for the rest of the war.

[S35] During the German spring offensive, there was a chance that No. 2 would be sent closer to the front. In preparation, the soldiers began military training a couple of times during the week and on Sundays, including rifle drill and training in trench warfare. Although No. 2 never had to deploy, this training continued till June, when the German threat had ended.

[S36] On July 1, 1918, the 11 CFC companies of No. 5 District and No. 2 participated in a sports day at nearby Chapois. No. 2’s band played throughout the day, entertaining spectators and participants. Two weeks later, the band played at a ceremony in Salins attended by French, American and Canadian troops to mark Bastille Day.

[S37] Shortly after the armistice of November 11, No. 2 received orders to report to the base depot at Etaples, on the channel coast. It departed Lajoux on December 4 and arrived in Etaples on December 7, where it was joined by the detachments from Alençon and Péronne. The company crossed the Channel on December 14 and went to Bramshott Camp, another location used heavily by Canadians in Britain during both World Wars. No. 2 was attached to the Nova Scotia Regimental Depot and its soldiers sent to various other camps that represented the military districts in Canada for return home. Some of the soldiers went to Kinmel Park in late December, a camp in north Wales that had a bad reputation and was the site of several demobilization riots in March 1919. Earlier, in January, a racially-motivated fight broke out, which involved soldiers from No. 2. Most of the drafts that made up No. 2 sailed in the latter part of January 1919, bound for Halifax. The unit was officially disbanded on September 15, 1920. 26 of its soldiers had died, mostly due to illness or accident.

[S38] During the war, the CFC produced nearly 814 million board feet of sawn lumber plus 1.114 million tons of other wood products. A board foot=12”x12”x1”; an average 3-bedroom house requires 14,000 board feet, so the CFC produced enough sawn wood to build 58,140 houses. Perhaps even more importantly, CFC operations freed up trans-Atlantic shipping space for different commodities: ammo, vehicles, reinforcements, food and fuel among many others. And the men of No. 2 played their full part in this vital undertaking. Major Sutherland received a letter from Major-General MacDougall, General Officer Commanding CFC, conveying the thanks of the CFC to the officers and men of No. 2 for their valuable and faithful service while attached for duty and discipline to the CFC.

[S39] I would now like to say a few words about remembrance—how No. 2 is remembered today—and various commemoration events for centennial celebrations in 2016 and scheduled for July this year.

[S40] Perhaps the first recognition of No. 2 was the dedication of the plaque on the right. It was unveiled in the main hallway of the Ontario Legislative Assembly at Queen’s Park on July 5, 1920 on the 4th anniversary of the unit’s founding and on the occasion of the 76th annual general convention of the British Methodist Episcopal Church, which brought together delegates from across Canada and the US. The project was spearheaded by a Toronto minister, Reverend Harry Logan, and his wife. They were the parents of one of No. 2’s soldiers, Private Harry Logan Jr. Sadly, Harry Jr died of pulmonary TB two years later.

[S41] The Black Battalion written by Senator Calvin Ruck and published initially in 1986 by the Society for the Protection and Preservation of Black Culture in Nova Scotia and in 1987 by a commercial publisher. It has as its sub-title “Canada’s Best Kept Military Secret.” Essentially, Ruck’s work is about the search for No. 2 veterans for a November 1982 reunion in Halifax. The actual story of No. 2 is covered in 7 pages, while its time in France consists of only one paragraph. The centennial reprint does not add to the story of No. 2 in France, but contains a thoughtful foreword by Lindsay Ruck, Calvin’s granddaughter. The value of Ruck’s work is in bringing awareness of the existence of the battalion out of the shadows and to a very wide audience. If, however, No. 2 Construction Battalion really was Canada’s best kept military secret, I believe that is no longer the case.

[S42] The Black Cultural Centre of Nova Scotia in Preston, near Dartmouth, has a permanent display that tells the story of No 2, which is being upgraded with new displays and interpretive panels.

[S43] In 2000, film-maker Anthony Sherwood, Reverend White’s great nephew, produced “Honour Before Glory,” an award-winning documentary film about No. 2, based on White’s diaries. Anthony is a member of the NAAC.

[S44] A memorial to No. 2 in Pictou was first suggested in 1982, but it took until July 1993 before a permanent memorial was unveiled not far from where No. 2 began its existence at the Market Wharf, Pictou. It was also declared a National Historic Site. Since then, an annual memorial service and parade has been held at the memorial and in the nearby Da Costa Centre. On July 5 this year, a new memorial, as well as an improved interpretive panel, will be unveiled.

[S45] A couple of recent studies provide more info about No. 2 than any other written works. I highly recommend an excellent article by Mathias Joost), whom I mentioned earlier, in the summer 2016 issue of Canadian Military Journal titled “No. 2 Construction Battalion: The Operational History.” It is based on the unit’s war diary and is available online. Mathias is a member of the NAAC. The book on the right is a very recent study of No. 2, published in 2018. titled “Black Soldier’s in a White Man’s War: Race, Good Order and Discipline in a Great War Labour Battalion” by recently deceased Halifax author Doctor Gordon Pollock. It’s an eye-opener. The 203-page book was published in the UK and at $120, it’s an expensive purchase. Pollock’s aim was to write a detailed history of the unit, warts and all, and critically examine the myth that he believes has grown up around No. 2. Pollock’s research was based on a pain-staking review of the service files of 587 soldiers, 537 of whom served overseas. The author’s review of files and court-martial records indicates that more soldiers in No. 2 received some form of military punishment than any other unit in the CEF. But these findings come with a caveat: Pollock details several occasions where findings of guilty and subsequent punishments were either clearly or likely based on racial prejudice. For example, Pollock estimates that the results of 40% of overseas courts martial in No. 2 were affected by race. And, as anyone who has served in the army will tell you—soldiers are not saints.

[S46] As part of its Hometown Heroes project during the centennial of the FWW, Parks Canada erected a number of billboards with stories of various Canadian men and women who served. In Nova Scotia, it included 4 soldiers from No. 2: George Downey, who served in both world wars (I showed a photo of him earlier with his cousin, James Downey) and Joseph Parris, the soldier in the middle of the group. I’ll have more to say about him later. The two other Hometown Heroes billboards from No. 2 were LCol Dan Sutherland and Reverend William Andrew White.

[S47] This is my favourite image of No. 2. I always feel that these men looking directly at us— straight into our eyes—from more than 100 years ago. Look at them. what qualities do you see? I know I see calm and confident men, proud to be wearing their uniforms, sure of themselves. There is seriousness, but also a bit of playfulness, a hint of a smile on some of their faces. I also see a bit of cockiness in the angle that some of them are wearing their caps. Look at them again. This image was chosen for many of the centennial commemoration items—and I am glad it was as I believe it’s an outstanding photo.

[S48] On January 27, 2016, at Province House in Halifax, the annual poster commemorating African Heritage Month for 2016 was unveiled. As you can see, it honoured No. 2 and was based on the photo. I always feel a bit sorry for the 5th soldier, who was standing on the far left of the original photo and did not get included on the poster or other centennial objects.

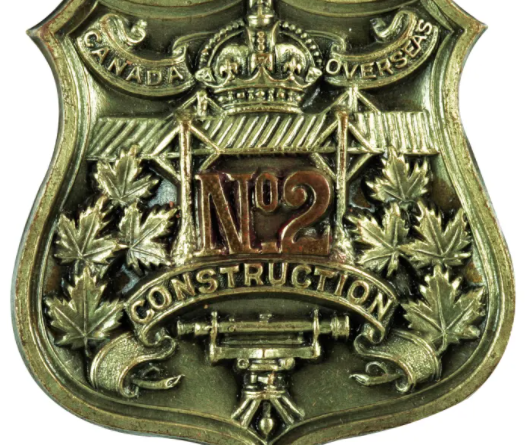

[S49] On February 2, 2016 at the BCC, Canada Post unveiled a first day cover and stamp in honour of No. 2 Construction Battalion. As you can see, the first day cover on the left depicts the badge of No. 2, an expanded image of soldiers walking through the woods and the stamp itself. The stamp on the right has the same background image, with the faces of 4 of the 5 soldiers in the photo superimposed on the trees.

[S50] Present at the unveiling were some of the descendants of Joseph Parris, a soldier in No. 2. The lady on the right is Sylvia Parris, daughter of Joseph, with some of her aunts and nieces. Sylvia is the CEO of the Delmore “Buddy” Day Learning Institute in Halifax.

[S51] With Sylvia’s permission, I’ll paraphrase and quote from a talk she gave: (quote) “One of the pictures often used to depict No. 2 Construction Battalion features Joseph Alexander Parris, my father. Seeing it always evokes emotions for me: pride, sadness, curiosity, disappointment. Certainly, he is a strapping figure in uniform. He looks self assured, a young man with purpose and resolve. On July 25, 1916, my father, at 17 (he would not be 18 for another 9 months) enlisted in No. 2 Construction Battalion. The men of the battalion put themselves, without access to weapons, in harm’s way by choice for a country that devalued them because of their race. How can we not be in awe of such a resilient and purpose-focused community? How can I not be in awe and puff with pride at such a resilient and purpose-focused man whom I called daddy?

How I would have loved to have asked daddy: what did it feel like to sail overseas? Did you miss your parents? These and many other questions I was not able to ask mainly because this important part of Canada’s and Nova Scotia’s history was not taught during my time in public school. We did not learn the full story of the war because we were not taught the story of the Black Battalion.

I think now of the conversations that I could have had by being able to say: daddy, today I learned in school about No. 2 Construction Battalion. The teacher said we should ask our families about it. Imagine what sharing that may have evoked” (unquote). Pretty powerful stuff, I think you’ll agree!

[S52] In 2016, Anthony Sherwood wrote a play about No. 2, titled “The Colour of Courage.” It tells the fictional story of four members of the unit—a white lieutenant and 3 black soldiers—trapped under fire in a trench and the trial that the soldiers force the officer to undergo.

[S53] In 2014, Halifax artist Richard Rudnicki completed this painting, commissioned by the Army Museum Halifax Citadel on the occasion of the bicentennial of the War of 1812. It depicts the so-called “Chesapeake Blacks” arriving in Halifax on a RN ship. These were people who escaped from slavery in the US and came over to the British side during the war. Although they were promised land and provisions in Nova Scotia, their initial years were very difficult, but the majority persevered and today make up the ancestors of the province’s original Black families, along with the descendants of the Black Loyalists who arrived earlier after the American Revolutionary War.

[S54] For the centennial of No. 2 in 2016, the Army Museum commissioned Richard to compose a painting symbolizing No. 2. At one of our regular Centennial Committee meetings, Richard showed a few rough sketches of his proposed painting. One of the committee members jumped from his chair, obviously agitated, and ran from the room. The sketch was similar to this final painting, except you could see a riding crop in the CO’s hand, he was mounted on the horse and the men working on the tracks were bare-chested. George Borden, since deceased, was a retired RCAF officer, poet and unofficial historian of No. 2. He later apologized for his outburst. When he viewed the sketch, he immediately saw a white overseer on a horse, keeping slaves in order. I think it’s called the law of unintended consequences. Needless to say, Rudnicki, a very mild-mannered man, was aghast that he had caused offence and immediately reworked the drawing to produce this. It was unveiled at the Army Museum on July 5, 2016. As you can see, Sutherland is standing beside his horse, the men have their shirts on and front and centre is Reverend White.

[S55] OK, here is the shameless author plug. I was also able to use Richard’s painting to illustrate the story of Thomas Goffigan in my 2019 book, “Amazing Atlantic Canadian Kids.” Thomas was only 15 when he joined No. 2 and even declared his true age, although 18 was the minimum age to enroll and 19 to be sent overseas. He was only a little over 5 ft tall and weighed 95 lbs. When he was released after the war, he was only 17 years and 5 months old—still too young to join!—but he had grown by almost 4 inches and gained more than 28 lbs. Sadly, Thomas died in 1921, a FWW veteran and only 19 years old.

[S56] On July 9, 2016, the centennial commemoration of the formation of No. 2 was held in Pictou. While the event is well-attended every year, because it was the unit’s 100th anniversary, there was a particularly large group of people in attendance. Representing the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) was Lieutenant-General Christine Whitecross, the first female in the forces to be promoted lieutenant-general, but even more importantly, the senior serving engineer in the CAF—and No. 2 was an engineer unit.

[S57] Here is a photo of 3 Honorary Colonels at the centennial ceremonies. That’s a rather dozy-looking me on the left as Honorary Colonel of the Halifax Rifles, with former Nova Scotia premier John Hamm as Honorary Colonel of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders and Honorary LCol Barry Wark, a retired army reserve colonel, as the unit’s Honorary LCol. The North Nova Scotia Highlanders parade at the memorial service at Pictou every year.

[S58] Although the centennial of No. 2 is over, the annual ceremony in Pictou in July 2017 commemorated another milestone: the centennial of the unit’s departure overseas in 1917.

[S59] In Sep 2018, this memorial was unveiled in the French town of Supt in the Jura Mountains. 10 members of the CFC are buried in Supt, including 4 soldiers from No. 2.

[S60] And now for something completely different…a bit of a coincidence 50 years after No. 2 was formed. The granddaughter of No. 2’s MO, Captain Dan Murray, who we all know as internationally-renowned singer Anne Murray, performed on the CBC’s popular Singalong Jubilee TV show with Reverend White’s son, educator and singer, Lorne White. They never knew about the connection until years later and are shown reuniting in Anthony Sherwood’s documentary.

[S61] Many of the pictures used in my talk came from the trunk on the left, belonging to Dan Sutherland. For years it was around the house of his granddaughter, Mary Beth Sutherland, on the right. She finally got around to having a look inside in the run-up to the centennial year and discovered dozens of pictures, as well as letters and other artifacts. Mary Beth has generously allowed the Army Museum to copy all the pictures in the collection to share with anyone who wishes them.

[S62] At the start of my talk I said I had been acting as liaison between the CAF Chief Military Engineer and the BCC. It has to do with the perpetuation of No. 2 by an existing Canadian Army unit. As some of you know, perpetuation of Canadian units is the direct result of the bizarre mobilization system dreamt up for the FWW by our obstinate, argumentative, opinionated, supremely self-confident, rabidly anti-French Canadian and anti-Catholic Minister of Militia and Defence, Sam Hughes (as you can perhaps tell, not one of my favourite people). Instead of following well-thought-out existing mobilization plans, Hughes opted to create a new plan off the top of his head. He did not mobilize existing militia units, but rather formed a series of numbered, soulless infantry battalions. This eventually created 260 numbered battalions, 4 mounted rifles battalions, plus 2 named ones, for a total of 266 infantry battalions, of which only about 60 were needed for the entire Canadian Corps of 4 divisions, including some that directly replaced depleted infantry battalions and others converted to pioneer or railway construction units. That left the remainder to the sad fate of being broken up in the UK for reinforcements to the corps in the field. After the war, this would have resulted in very few units actually being awarded FWW battle honours. Enter the Otter Commission in 1919, which tied numbered CEF battalions to militia battalions, largely based on recruitment and geography. Although Sutherland attempted to have No. 2 remain as a unit of the militia after the war, his request was denied as no CFC, construction, labour or railway troops were continued after the war. A few years ago, a proposal was submitted up the CAF chain of command, requesting perpetuation of No. 2 by an existing Canadian Army unit, 4 Engineer Support Regiment, stationed at CFB Gagetown. The Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) has approved this, which will be announced on July 9, along with the battle honour “France and Flanders, 1917-1918.” This will allow the legacy of No. 2 to be perpetuated by an existing, regular force engineer unit. I can assure you this will be very meaningful to the descendants of the soldiers who served in No. 2.

[S63] For some reason, over the years there has been a tendency to try to embellish the story of what No. 2 did overseas by alluding to its involvement in frontline operations. But No. 2 was not a frontline combat unit. It did not dig trenches at the front, defuse land mines ahead of advancing troops, lay barbed wire, carry wounded soldiers from the battlefield or engage in combat operations. To state otherwise is simply wishful thinking that is not backed up by the historical record. Members of the NAAC have been instrumental in changing such errors as they become aware of them.

[S64] As many of you know, in the military we have something called the tooth-to-tail ratio. It simply means the number of support troops required to keep one combat soldier fed, clothed, watered, supplied with ammo, transported, paid, treated medically and dentally and so on. A typical ratio for one soldier at the front might be anywhere up to 10 more behind him all the way to the rear areas and beyond, even to the home country. While every unit had limited built-in support, the farther back from the front, the more a unit would be devoted to support, until we get some units that were 100% support. Some of these units in the CEF are shown on the right: construction, labour, pioneer, railway construction and forestry units. But even if 100% support, every unit had to be prepared to defend itself and fight if necessary.

[S65] My point is that we do not have to make up or embellish stories about what the men of No. 2 did during the FWW. Whether front line or rear area, all soldiers of the CEF had a part to play in the war. The CEF was like a giant engine and if any one piece was missing then the whole simply did not run smoothly or run at all. The motto of Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians), the armoured regiment that I commanded when I was serving is “Perseverance.” It could very well be the motto of No. 2 as well, because the record of what the soldiers of No. 2 accomplished in the face of overt prejudice stands on its own as an outstanding example of perseverance.

[S66] Turning now to the apology, on March 28, 2021, then Minister of National Defence (MND) Sajjan announced the long-overdue decision of the Canadian government to apologize to the descendants of No. 2 for the racism and discrimination their ancestors faced in attempting to join the CEF, during their service and afterwards. This decision was reaffirmed by new MND Anand exactly one year later, on March 28, 2022.

[S67] Canada has a history of formal government apologies stretching back at least to 1988, as shown here. In most cases, they were issued by the PM in the House of Commons. Certainly, for any apology to an ethnic group, nationality or race, they were delivered personally by the PM. Others have been delivered by MND, such as FWW executions, while sexual harassment/assault within DND was from MND along with CDS and Deputy MND. Uniquely, the Acadian Deportation apology was by a Royal Proclamation from the Queen because of the dates of the Deportation. The Kogata Maru apology appears twice, as the first time was not in the House, while the second was. Several apologies came with direct and/or indirect financial compensation. As an aside, it seems strange to me that the federal government has taken so long to apologize to the Black community, and then not to all Canadians who experienced historic anti-Black racism. Perhaps this will happen in time.

[S68] To develop and oversee the apology process, a National Apology Advisory Committee was formed after MND’s initial announcement, under the joint chairmanship of the BCCNS and the Canadian Army, with representatives from the BCC and the army, plus No. 2 descendants, historians, activists and others. The NAAC has 3 main sub-committees: Communication and Community Outreach, History and Public Education and Logistics, plus one per Atlantic, Central and Western Regions.

The NAAC has met frequently and in particular has engaged in a number of highly-successful national consultative break-out sessions by video to hear from the grassroots level what should be included in the apology, what would make it meaningful, what events should be a part of the apology and what legacies should the apology event leave, among many others. A report summarizing the results of these consultations has just been presented to MND.

[S69] I think I’ve spoken for long enough. Thank you for your attention. I hope that I have added to your knowledge of No. 2 Construction Battalion and what its members achieved, despite racism and discrimination, as well an explanation of the extensive apology process. I look forward to any comments you may have, as well as attempt to answer your questions.