The National Shipbuilding Strategy Needs to be Revamped

In 2003 John Manley, then federal government Minister of Finance, said that shipbuilding in Canada was a “sunset industry” and that Canada could not afford huge subsidies for shipbuilding. Seven years later, Rona Ambrose, then federal Public Works minister, said that the National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS) would renew the fleets of the Canadian Coast Guard and the Royal Canadian Navy. Quite a turnaround!

Now we are at the end of 2017 and the only operational vessel that we have seen is the Motor Vessel (MV) Asterix, a commercial vessel to be chartered to the RCN as an interim replacement for the Navy’s retired replenishment oilers (in naval terminology, AOR). And, Asterix was not built by one of the two shipyards named as prime contractors in the NSS!

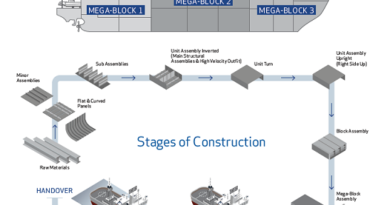

The two prime contractors, Irving Shipbuilding Incorporated of Halifax, NS, and Seaspan Marine Group of Vancouver, BC, have suffered delays while rebuilding obsolete facilities and awaiting clear direction from the federal government. Priorities and schedules have changed during that time leaving the needs of the Coast Guard and the Navy unmet, and at the same time diverting already limited funds to refits required to prolong the service lives of vessels that should be replaced.

Refits of older vessels are expensive because of the requirement to conduct steel replacement, and modernize electronics and power amongst other issues. Life extension projects take the vessel out of service for prolonged periods and incur additional costs through having to source out-of-production parts and equipment or installing new equipment for which those vessels might not have been designed.

Why does Canada have the money to preserve obsolete ships but not to build new ships? That is not a fair question, however; it isn’t the financial issue that is the problem, it is the fact that Canada does not yet have the willingness to modify the NSS to include more shipyards or to modify vessel requirements.

The Asterix is an example of what could be accomplished with more shipbuilding capacity. The RCN needs more than one AOR, in fact it needs three (remember the Preserver, Provider and Protecteur?): one on each coast and one to respond to replacement for refits of the other two. And to take it a bit further, the third one, when available, could be utilized to replenish Coast Guard icebreakers and RCN vessels working in the Arctic during the summer months.

So what is wrong with having Chantier Davie, or another yard, converting two more replenishment vessels on budget and on time as well as at a much reduced cost relative to the Joint Support Ships (JSS), the projected AOR replacements? And why doesn’t the federal government purchase them as opposed to chartering? The resulting cost savings could then be used to build the seemingly forgotten JSS or to increase the funding available for the warship replacements which should be a priority.

Canada’s largest icebreaker, CCGS Louis S. St.-Laurent, will be 50 years old in 2019. Yes, she had a major mid-life refit during which her bow was replaced and she was re-engined from steam turbine to diesel electric. However, since then she has been to the North Pole three times, and conducted icebreaking in the Arctic and Gulf of St. Lawrence winter and summer over those years. There was talk of a Polar 10 nuclear icebreaker, later downgraded to a conventionally powered Polar 8 but built to serve all government departments in the Arctic during a nine month operational season. The Polar 8 was cancelled in 1990 at the last moment and progress on a replacement has proceeded slowly. The latest development has the new major icebreaker being “bumped” in the production line by the requirement to build two more AOR after three science vessels are completed by Seaspan. This will result in at least late next decade before a replacement is put in service. And that is only one icebreaker. CCGS Terry Fox, Canada’s second most powerful icebreaker, was built in 1983 as a commercial Arctic drilling support vessel for Gulf Canada, was leased by the Coast Guard in 1991 and purchased outright in 1993. The remaining type 1200 icebreakers were built in the late ‘70s and are approaching replacement requirements. Costs increase with every delay. There is no mention of them in the NSS.

Building the Arctic Offshore and Patrol Vessels (Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ship project) is delaying yard capacity for building the frigate replacements. As an outsider, the AOPV appear to be designed neither as actual icebreakers nor as interdiction vessels. At best, they may fulfill a role as ice-strengthened training vessels or Kingston-class (Maritime Coastal Defence Vessel project) replacements. Perhaps the production should be limited to three vessels with the resultant savings being reassigned to the frigate replacement project. And, in order to speed up that project, Canada should speed of the process of looking seriously at warships used by allied nations that respond to the 80% rule of meeting our identified needs. The design cost savings and inter-changeability of units with allies could prove invaluable in meeting Canada’s NATO commitments. We have done that successfully with other military acquisitions. Those savings might also mean that we could build some larger warships as command units to augment the RCN’s capability.

The NSS should be realigned to meet the changed needs of Canada’s marine departments. A third shipbuilding yard is an absolute necessity, and the changing requirements of the Coast Guard and Navy need to be addressed.

Jim Calvesbert is a retired Canadian Coast Guard officer, having served at sea and ashore. He is a graduate of the Canadian Coast Guard College and holds a B.Ed. from the Université de Moncton, a Masters degree in Marine Management from Dalhousie University, and is a member of the Master Mariners of Canada. As a consultant, he has worked nationally and internationally in the marine field. This work is the sole opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of the Canadian Armed Forces, the Canadian Department of National Defence, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Canadian Coast Guard or the Royal United Services Institute of Nova Scotia. The author may be contacted by email at: RUSINovaScotia@gmail.com.

Photo: Public Services and Procurement Canada.

PDF of this Comments.