Recruiting and Retention in the Reserve Force

by David Swan

Recruiting and retention of Reserve Force personnel has been a problem for many decades. Recruiters know that people who join the Reserve Force say ‘they want to serve.’ Historically, personnel tended to leave in groups at specific times: many after three years of service, more after six years of service, and a few more after twelve years of service. The services know how to train their personnel to bond, yet there has been a reluctance to apply those tools to the Reserve Force.

The most successful example of recruiting and retention I know of belongs to Air Reserve squadrons. In the 1980s there were ‘twinned’ squadrons (Regular Force and Reserve squadrons with the same airframes and same missions), including a search and rescue squadron in Edmonton and a maritime reconnaissance squadron in Summerside. The squadrons averaged 110% of authorized strength.

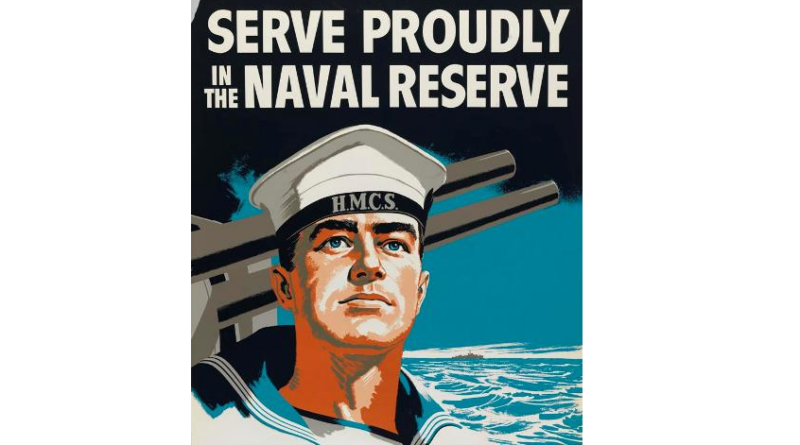

I was recruited into the Naval Reserve at HMCS Carleton, Ottawa, and served at HMCS Griffon, Thunder Bay. Both of those units were typically above 90% of authorized strength and were usually in the competition for best unit in the Naval Reserve. Both units also had a strong focus on manning ships (Gate Vessels). In the Army Reserve, some units had ‘picked specialties’ such as ‘urban warfare.’ These ‘focused’ units saw improvements in recruiting and retention.

The takeaway is the closer reserve units get to ‘doing their job,’ the better for recruiting and retention. Events such as the ‘Ice Storm’ of 1997 and the SwissAir crash of 1998 were perceived as net positives for recruiting and retention because of the impact of being deployed ‘for real.’ Reserves got to do their jobs. The Army Reserve contributed massively to Afghanistan deployments, in part because they got to do their jobs, deploy for real.

‘Augmenting the Regular Force’ has been the standard method of incorporating reserve personnel into the Regular Force. It has a consistent record of not working for the Reserve Force. There is no unit recognition, little or no impact of returning personnel on their units, and limited recognition of Reserve personnel. Worse, when personnel are deployed individually, they are often scorned by their Regular Force counterparts.

If recruiting and retention of the Reserve Force is a serious issue, mission oriented team training and team employment need to be implemented. It’s not a universal cure, but it could be an effective starting place.

David Swan is a retired officer of the Canadian Armed Forces.