Canadian Corvettes in the Second World War – A General History

by Dr Richard H. Gimblett, MSC CD RCN (ret’d)

The humble corvette was not meant to be the mainstay of Canada’s naval effort in the Second World War. For that matter, when Hitler invaded Poland on the 1st of September 1939, no one had any idea that the unfolding European land war would expand into a global conflict requiring an oceanic lifeline from North America to Europe that has been immortalized as the Battle of the Atlantic. Still, the Canadian naval staff immediately appreciated that the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) would not have enough ships for whatever might arise – the entire fleet then consisted of only thirteen ships: a half-dozen frontline River-class destroyers, four modern Fundy-class minesweepers, a pair of Battle-class trawlers left over from the First World War, and a sail training vessel. Six years later, almost to the day, when peace with Japan was signed on 2 September 1945, the RCN had grown to be the fourth-largest allied fleet (behind the United States, United Kingdom and Soviet Union), with nearly 100,000 men and women in uniform, and over 400 warships in commission. By then corvettes constituted a full quarter of the combat fleet, with 123 having been in commission, and ten of those lost in action. Indeed, the corvette had proven to be one of the largest Allied shipbuilding programmes with a total of 368 ships of eight different sub-types being built in Britain (186), Canada (122) and Australia (60).

The rearmament problem in the fall of 1939 was twofold – what type of vessel to get, and where to get them from? (A third issue – how to crew them? – was not yet fully appreciated.) The major British yards were at capacity building aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers and destroyers already ordered for the Royal Navy (RN); all of these major warship types were beyond the capacity of Canadian shipyards, nor had a lend-lease arrangement with the neutral United States yet been conceived let alone put into place. In the end, a solution arose from the fact that the RN also was facing a shortage of auxiliary coastal escorts and had developed a type that could be built in smaller British yards that lacked the technical sophistication to build capital ships. The “patrol vessel, whale-catcher” is said to have been re-designated “corvette” by Sir Winston Churchill, who then was First Lord of the Admiralty before becoming prime minister in May 1940. He also more famously dubbed them “cheap and nasties.”

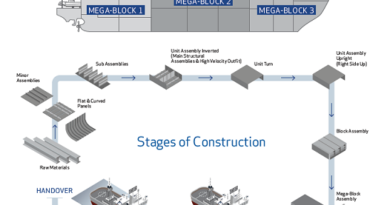

Indeed, the vessel was an adaptation of a commercial design that was assessed to be inexpensive and easy to produce for emergency “hostilities only” production. This small, 205-foot long, 950-ton displacement, single-screw, steel hull ship fit the capacities of most Canadian shipyards, which had never built a steel-hulled warship greater than 100 feet (30 metres) in length. The design had the additional advantage that any production in the large number of Canadian shipyards on the Great Lakes had to be shorter than 270 feet (82 metres) to fit through the locks on the St Lawrence River before the Seaway was completed in the mid-1950s; there remained, however, the limitation that these yards were iced-in over winter, so that while production could continue, the ships couldn’t go down the St Lawrence River for fitting out and to enter service until after spring breakup. The corvette’s machinery was similarly modest and within the capacity of Canadian industry: two low-pressure drum water-tube boilers provided steam to a 2,750-horsepower four-cylinder vertical triple-expansion engine, giving a range of 3,500 miles at 12 knots (which dropped to 2,500 miles at maximum speed of 16 knots).

Ship classes generally are known by the name of the lead (first built) ship, which in the RN was HMS Gladiolus, completed in April 1940. With all of the RN vessels getting similar names, the corvettes become known more popularly as the Flower class. That general term held in the RCN as well, even though the Canadian Chief of the Naval Staff, Rear-Admiral Percy Nelles, observing that “flowers don’t knit mittens,” instead directed the ships be named after cities and towns to make the naval war effort resonate with the populace. The initial Canadian order of 54 under what became known as the “1939-40 Program” were completed as auxiliary minesweepers with a wider quarterdeck giving them a broad somewhat square stern distinguishing them from the duck-tail shape of RN corvettes; follow-on orders for the 1940-41, 1942-43 and 1943-44 programs dropped the minesweeping capability and adopted the more familiar British form.

As the war continued, other changes to the basic design were incorporated as a result of operational experience. By the time the first Canadian-built corvettes commissioned in October 1940, Hitler’s forces had occupied Norway and France and established U-boat bases within easy reach of the North Atlantic, shifting the need for escorts to the open ocean. Corvettes already had gained a reputation that they “would roll on wet grass” but the dramatic change of role quickly brought home the fact that the short fo’c’sle (forecastle) with a well-deck opening ahead of the bridge made them a very “wet” ship. To attempt to overcome this, the major modifications of the “Revised Flower Class 1940-41 Program” included extending the fo’c’sle aft to form an enclosed deck from the new flared bow back in line with the funnel; this required in turn that the forward 4-inch gun and the bridge had to be raised a full deck, and eventually the foremast located inconveniently in front of the bridge was moved back behind it, all dramatically changing the appearance of these later ships. Earlier-built ships eventually were modified to this new standard as operational requirements and shipyard capacity allowed; for example, Sackville (which will be discussed below), commissioned in December 1941, was not so refitted until February-May 1944. Still, the corvettes of the first two years’ building programs suffered from poor range. This was resolved by a change to a more compact boiler type that allowed for additional fuel tanks, classifying the 1942-43 and 1943-44 programs as “Revised Increased Endurance” programs, giving them very long legs of 7,400 miles at 10 knots.

Some major deficiencies that were never overcome in the Flower class included their lack of a gyro compass for accurate navigation (the fitted magnetic compasses did not follow “true” north and had a lot of swing in the bearings indicated). They were saddled as well with Canadian-designed radars and sonars that were not as accurate as later British developments, all of which hampered a corvette’s ability to conduct accurate underwater attacks on submerged U-boats. This was rationalized against the fact that their primary benefit was their just being on scene, offering the threat that any sort of surface escort was sure to give a U-boat pause in attacking.

The shortcomings of the corvettes were never fully resolved until the design in 1943 of what at first was styled the “twin-screw corvette” – soon designated as a “frigate” – that was some 100 feet longer and 500 tons heavier, could carry greater armament and variety of sensors, and came equipped with a gyro compass. These proved too large to be built in the yards above the St Lawrence Canal locks (and for the smaller British yards), so a scaled-down version of shorter length and back to a single screw was developed (252 feet and 1,060 tons); although an altogether different ship from the original Flower class, they generally are included in discussions of “corvettes” and were named the Castle class. Orders were placed for 37 of them to be built in Canada, but these all were cancelled in favour of other types; of the 12 commissioned into the RCN all were built in British yards. Another sub-group of “corvettes” often overlooked were the 60 ships of the Bathurst class built in Australia, essentially to Revised Flower-class specifications (that is, with the extended fo’c’sle, but somewhat shorter at 186-feet length).

A full discussion of the operational employment of RCN corvettes would take more space than is allowed here. The majority were allocated to the “North Atlantic Run”, but a good number were detached at various times for such operations as the Caribbean oil convoys (from early 1942), the Aleutians (spring and summer of 1942 and 1943), the Battle of the Gulf of St Lawrence (in the summers of 1942 and 1944), Torch (the invasion of North Africa, November 1942 – January 1943) and Neptune (offshore support for the invasion of Normandy, May-August 1944). In exchange for the 10 lost in action, RCN corvettes participated in the capture or destruction, alone or in company, of 14 German U-boats.

Within a year of the end of the war, demobilization saw the bulk of the worn-out little ships disposed of for scrap, with a few going to smaller Latin American and Asian navies. Only one was kept on in Canadian government service, the former HMCS Sackville, transferred to the Department of Transport as a civilian oceanographic research vessel until finally being paid off in 1982. The volunteer Canadian Naval Memorial Trust quickly was established to acquire and restore the ship to her mid-1944 configuration. In 1985 the Canadian Government approved the restoration of her identity as a “His / Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship” and designated HMCS Sackville as Canada’s Naval Memorial, dedicated to the 2,000 sailors who lost their lives at sea. As “the last of the Flowers” she is berthed on the downtown Halifax waterfront and is open to visitors all summer as part of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic complex.

Sources

Online:

James Brun, “The Flower-class Corvette – Nine Facts about the Tiny Warship that Played a Huge Role in WW2”.

Brian Dubreuil, “HMCS Sackville,” Canadian Encyclopedia.

Marc Milner, “The Humble Corvette,” Legion Magazine, June 2008.

HMCS Sackville – Canada’s Naval Memorial.

Wikipedia, Flower-class corvette.

Wikipedia, List of Flower-class corvettes.

Wikipedia, Castle-class corvette.

Wikipedia, Bathurst-class corvette.

Immortal Wordsmith: Churchill’s ‘Cheap and Nasties’.

Books and articles for further reading:

E.H.H. Archibald, The Fighting Ship of the Royal Navy, 897-1984 (New York: Military Press, 1987).

W.A.B. Douglas, Roger Sarty and Michael Whitby (et al), A Blue Water Navy: The Official Operational History of the Royal Canadian Navy in the Second World War 1943-45, Volume II part 2 (St Catherines, Ontario: Vanwell, 2007), “Appendix III – Axis Warship Losses to Canadian Forces, 1939-1945,” pp. 568-70.

Donald G. Graves, In Peril On the Sea: The Royal Canadian Navy in the Battle of the Atlantic (Robin Brass, 2003), published for the Canadian Naval Memorial Trust (HMCS Sackville) and available in segments on the CNMT website: https://hmcssackville.ca/the-ship/in-peril-on-the-sea/.

Thomas G. Lynch, “Canadian Corvettes: Concept & Development,” in Random Thoughts,13:5, pp. 103-4.

K.R. (Ken) Macpherson, Canada’s Fighting Ships (Hakkert, 1975 / Canadian War Museum Historical Publication 12).

Ken Macpherson & Marc Milner, Corvettes of the Royal Canadian Navy, 1939-1945 (Vanwell, 2000).

Ken Macpherson & Ron Barrie, Ships of Canada’s Naval Forces, 1910-2002 3rd edition, Vanwell, 2002).

John McKay & John Harland, Anatomy of the Ship: Flower-Class Corvette Agassiz (Vanwell, 1993).

James Pritchard, A Bridge of Ships: Canadian Shipbuilding during the Second World War (McGill-Queen’s, 2011).

Dr Richard Gimblett is a retired naval officer and historian of the Royal Canadian Navy. This work is the sole opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of the Royal United Services Institute of Nova Scotia, the Canadian Department of National Defence, the Canadian Armed Forces or any other government department or agency. The author may be contacted by email at RUSI(NS).

Picture of HMCS Sackville attacking a U-boat, courtesy of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Halifax, Nova Scotia, a part of the Nova Scotia Museum.