Naming and Renaming Canadian Warships

Reference: Canadian Warship Names, David J Freeman, 2000

Warships are major symbols of statehood. A warship in commission can be thought of as an ambassador of the state. The ship’s movements and her sailors represent the diplomacy and the values of that state. A warship off a coast or visiting a port is seen as action by that state, and in the eyes of observers a ship’s name is closely linked to the state.

A warship’s name can have historical and geographical connotations that are important to a country. The name can also have political, social and ‘messaging’ purposes.

A ship is also a home for those who sail in her. A warship’s name is a connection to the honours won and to the accomplishments of those who sailed before in ships of the same name.

So the name of a warship is chosen carefully before that ship is actually named and launched in a ceremony1 harking back hundreds of years. Given the significance of the name, the decision of what to name a warship is rightfully a government’s to make, in the case of Canada made by the Minister of National Defence. When appropriate, the Minister decides when to rename a ship, with the advice of the navy’s senior leadership.

The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) has an internal guide for the naming of different types of ships (frigates, submarines, etc.) which staff use, with additional direction from senior leadership, to prepare proposed names for new ships. Proposals are considered by senior naval and government authorities, and submitted to the Minister of National Defence who makes the final decision. That decision need not conform to practice, as happened with Kingston and sisters of her class built under the Maritime Coastal Defence Vessel project. The ships, as mine warfare vessels (though they more often serve as multi-role patrol), could have been named after bays and other coastal formations, but instead were named after cities and towns, as had the Halifax-class frigates before them. In the case of the frigates, city and town names were in accordance with the guide. With frigates, Kingston-class, and Victoria-class submarines, all named after cities and towns, the RCN is in a good position to connect to the Canadian public.

A warship naming announcement is just an announcement, not even something usually recorded in reference publications which list warships. Until the actual naming ceremony occurs, an announcement is just an intention. Once named, a warship often retains the name (historically sometimes even when captured) until sent to the ship breaker, the name being struck off registries and listings when the ship is so broken up as to be unable to serve any longer as a vessel.

There can be a number of reasons for renaming a warship after a naming announcement and even after a naming ceremony or commissioning of the ship into naval service. There are many precedents in the RCN; renaming often occurred when ships built or building for another navy (e.g., Royal Navy) were transferred to Canada.

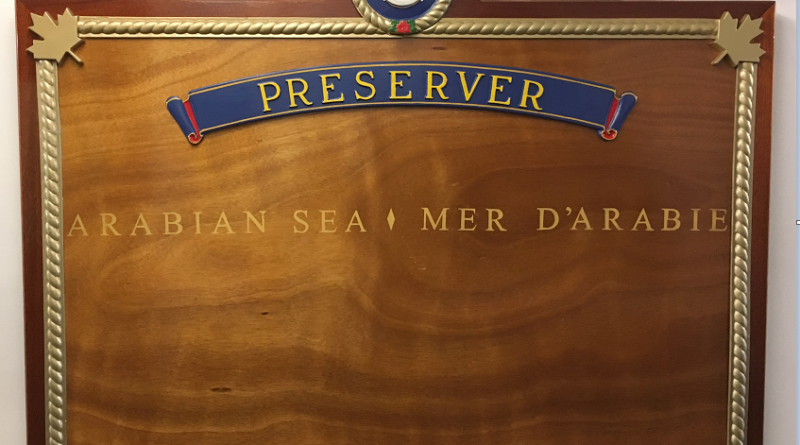

When a warship receives the name of a warship that served before in the RCN, artifacts from the previous ship(s), such as the ship’s bell, pass to the new ship. The board listing battle honours of the previous ship may be inherited, too, or a new copy of the board made. In either case, the honours, decades and in some cases longer past, are borne by the new warship with pride.

The book “Canadian Warship Names” is a comprehensive compendium of information related to the naming of Canadian warships.

Note: 1. The naming ceremony was once known in Canada, and is still known in other countries, as a christening.