Common Law, Civic Law, Martial Law and Military Law

by Major Tim Dunne, Canadian Armed Forces (retired)

To understand the evolution of military justice it is necessary to look at early English military governance. Many writers begin this analysis with the 1689 Mutiny Act by William III (William of Orange), but the analysis needs to go back farther to the roots of the English legal system which comprised common law civic law and martial law, such as it was coming from the fourteenth century.

Common law is the legal jurisdiction that evolved and developed through judicial decisions and court precedents rather than being codified in statutes or written legislation, and is the basis of legal jurisdictions in many countries that were colonies of the British Empire, such as Australia, Canada, England, New Zealand and the United States, except Louisiana. Louisiana is not a common law state because, like Quebec, the state derives its laws from the Napoleonic Code and is a composite of the French and Spanish versions.

The primary differences between civil and common law “lie in the implementation and interpretation of the law.”[1] Common law employs what’s known as stare decisis, a Latin term that means “to stand by the things that have been decided” and is the legal principle that determines the precedence for verdicts where the outcome of similar, foregoing cases may affect those currently before the courts. Civil law is more codified and based on “direct interpretation of the law or legislation applicable to the specific legal situation.”[2]

The principal characteristics of common law, recognized as unwritten law, are that they are drawn from the decisions of judges in previous individual cases, establishing precedent (stare decisis); over time, these decisions create binding precedents for future cases with similar facts or legal issues; and the courts follow the decisions of higher courts within the same jurisdiction, seeking consistency in the application of law. Unlike statutory law, which is created by legislation, common law derives from customs, traditions and previous judicial rulings.[3]

History of Common Law

Medieval England: England began its rise with William III’s (William the Conqueror) Norman invasion and the Battle of Hastings of 1066. The evolution of common law followed as the king’s judges travelled throughout England to address disputes, apply consistent rulings and create a unified system of law, developing the foundation of English common law. As these courts ruled on the matters placed before them, they recorded their decisions, which became references and precedents for similar disputes. Gradually, this body of precedent became the framework for legal principles in England and spread to other regions through colonization and became the basis for legal systems in many English-speaking nations.

Common Law versus Statutory Law

Common Law has evolved through preceding court decisions on related issues. Common law is dynamic and adaptable, changing, developing and evolving as contemporary courts interpret existing precedents in light of new facts and societal norms. Statutory Law is created by legislatures, Governor-in-Council and regulatory agencies and is codified in written statutes which courts interpret and apply and can override common law.

Common law is often applied in areas where statutes are silent or ambiguous, such as contract law, tort law (e.g., negligence, defamation), property law and criminal law (to some extent, though most modern criminal law is codified).

Significant attributes of common law include precedence based on preceding judicial decisions over similar matters; flexibility as it adapts to changing societal needs through judicial interpretation; judicial independence as judges play a central role in shaping the law based on reasoned decisions; and influence as common law principles, such as the right to a fair trial or the presumption of innocence entrenched in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the criminal code have significantly affected the Canadian criminal justice systems.

Civil Law Systems are based on the comprehensive written codes, such as Canada’s criminal code which judges apply with less flexibility to establish legal principles and precedent.

Martial Law and Military Law

The distinction between martial law and military law in England evolved gradually over several centuries as legal frameworks became more structured and formalized. In the medieval era, the English monarch and government did not formally distinguish between “martial law” and “military law.” Both referred to the discretionary authority exercised by military leaders to maintain order, frequently during times of war or rebellion.

The Court of Chivalry originated in the Middle Ages as part of the enforcement of the laws and customs of chivalry. Initially, the Earl Marshal of England and, at times, the Lord High Constable presided over the court until after the 14th century when the Earl Marshal alone held jurisdiction.

This was a civil, not a military, court concerned with matters relating to knighthood, heraldry, and certain aspects of military law and the traditions of chivalry and feudal obligations. The jurisdiction of the Court of Chivalry was continuous, in both peace and war, while a state of war was required before martial law could be invoked. The Lord High Constable or the Earl Marshal of England had, at times, during the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries, executed rebels under martial law, but this was distinct from and independent of their duties in the Court of Chivalry. Following the accession of Henry VII the operations of the Court of Chivalry declined, and by 1496 the court has ceased functioning.[4]

Development of Military Law

Military law, as a specific legal code for soldiers, began to evolve in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with the amplification of the Articles of War by monarchs of that period such as Henry VIII and later, Oliver Cromwell with his New ModelArmy during the English Civil War (1642 – 1651). The first Articles of War were prepared by Richard I to govern the discipline of English soldiers deploying to the Third Crusade (1189-1192) in a system that was separate from the civilian legal system.

Martial law encompassed the use of extraordinary powers by the sovereign or commanders to maintain public order during emergencies. English kings during this time often preferred prosecution of rebels under the Court of Chivalry as their property and wealth would be assumed by the monarch.

Parliamentary Regulation

The Mutiny Act, first passed by William III and Mary II in 1689, was a major step in in the separation of martial law and military law. The Act provided legal authority for maintaining a separate military disciplinary system. It established a formal system, jurisdiction and an early disciplinary code for soldiers subject to parliamentary oversight. Martial law, on the other hand, began to be viewed more as an emergency measure, used in extraordinary situations to govern civilians or impose military authority during times of rebellion, invasion, or other crises.

Over time, military law was codified and applied specifically to members of the armed forces. It was formalized through acts like the Army Act 1881 which consolidated military discipline laws for the British Army. This was the body of military law that governed British, Dominion, and Colonial armies during the First World War.

Martial law became increasingly controversial when applied to the civilian community as it often involved suspending normal legal rights. Legal theorists and lawmakers sought to apply boundaries and restrictions, defining it more narrowly as an exceptional measure for emergencies rather than a standard practice. By the 20th century, the separation had become formalized with military law a permanent and structured body of law governing armed forces. and martial law, an extraordinary and temporary measure, subject to strict limitations and often controversial due to its suspension of civil liberties.

[1] Bloom, Seth. “What Is Unique About Louisiana Law?” Bloom Legal, January 16, 2019. https://www.bloomlegal.com/blog/what-is-unique-about-louisiana-law/

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid.

[4] Capua, J. V. “The Early History of Martial Law in England from the Fourteenth Century to the Petition of Right.” The Cambridge Law Journal 36, no. 1 (April 1977): https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008197300014409. P. 158.

Major Tim Dunne (ret’d) is a veteran of 37 years as a Canadian military public affairs officer. He is writing the book “Jaded Justice: a history of Military Justice from 1066 to Today.” This work is the sole opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of the Royal United Services Institute of Nova Scotia, the Canadian Department of National Defence, the Canadian Armed Forces or any other government department or agency.

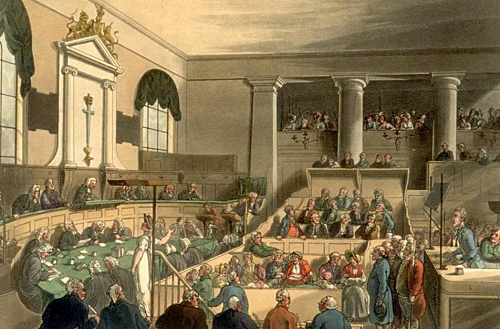

Image: An Old Bailey trial, circa 1808 Wikimedia Commons